As a rule, I rarely go to see musicians I haven’t heard. My tastes are way too idiosyncratic and polarized — despite the best efforts of “You may also like…” algorithms, I still remain determinedly indifferent to, for example, Guided By Voices — and I’ve learned that I don’t really enjoy seeing bands that I’m not already sure will hit my musical sweet spot. With Chuck Prophet, I got lucky.

As a rule, I rarely go to see musicians I haven’t heard. My tastes are way too idiosyncratic and polarized — despite the best efforts of “You may also like…” algorithms, I still remain determinedly indifferent to, for example, Guided By Voices — and I’ve learned that I don’t really enjoy seeing bands that I’m not already sure will hit my musical sweet spot. With Chuck Prophet, I got lucky.

Back around the turn of Y2K, a window opened for me into a motherlode of music via the wonders of CDR trading. In those days of the growing-but-still-low-bandwidth internet, music lovers could share lists of what they had in their hoarded collections of live concert recordings — often transcribed from handwritten or typed lists onto freshly composed “Web sites” — but to actually send music files over wires would of course take impossibly long. Not having a fleet of tractor-trailers at our disposal, we instead turned to the U.S. Postal Service, and burned and mailed each other CDRs — a huge upgrade over the cassette tapes that were the standard medium of just a couple of years earlier — containing live and radio recordings that would otherwise remain trapped on dusty shelves in another part of the world, far from our ravening ears.

Somewhere in there, someone I had swapped a few discs with realized I lived in New York City, and could record shows off the radio that he wanted to hear but would never be able to, obviously, because he was in another part of the world. He would send me lists of upcoming shows, and I would dutifully tune my radio to WFMU or WFUV at the appointed hour, bending the wire antenna this way and that to try to minimize the unavoidable static. I don’t even remember all the bands I recorded at his request, but I’m pretty sure there were appearances by the Moldy Peaches, by the folksinger Lucy Kaplansky, and by a guy with a funny name: Chuck Prophet.

I hit record on whatever next-generation recording device I had at the time (probably a minidisc, magical for being able to record 70 whole minutes without tape hiss and only minimal digital compression), burned the results to CD, mailed them off, and forgot all about them.

Leap forward to a somewhat later part of prehistory: 2009. Mindy and I were looking for somewhere to go for an evening out with our music-loving friends Josh and Lisa, and as I scrolled through a list of upcoming shows — in a few short years, music listings had jumped from ads in the Village Voice to listings you found on your computer — up popped the name Chuck Prophet. I vaguely remembered him as being someone who was supposed to be cool, or at least no less cool than Lucy Kaplansky. As this was in the days before you could fire up Spotify or YouTube and hear anyone you wanted, and anyway we were just looking for someplace to go spend what had become a rare kid-free night out, I figured, what the hell. At least the venue, a former 99-cent store turned rock club called Southpaw, was close to home if we wanted to bail early.

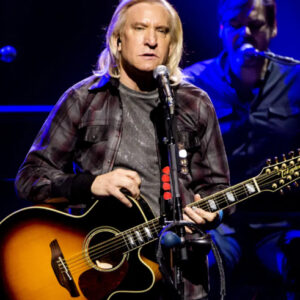

Reader, we did not. From the ridiculously hooky opening guitar crunch of “Sonny Liston’s Blues,” the lead track off Chuck’s then-new album ¡Let Freedom Ring! — to this day, one of my favorite guitar sounds of all time, to the point where I even bought the same pedal he uses so I could try to emulate its tone on the rare occasions when I play guitar — I was won over. Chuck and his band the Mission Express rocked, they grooved, they had witty lyrics and wittier stage banter and a secret weapon in Chuck’s keyboardist/backing vocalist/spouse, Stephanie Finch, who stepped out front mid-set for her own solo song. At one point Chuck went off on a long speech about how he had been informed by security that some audience members might be illicitly recording the show, and he hoped that those people would have respect for the needs of a working artist … and be sure to include this next song, because it was a new one and it needed the publicity. How had I missed this guy for the previous 20 years?

We stayed to the very end, past the show-stopping show closer “You Did (Bomp Shooby Dooby Bomp)” and into whatever garage-rocky covers Chuck had lined up for the encore, and I’m pretty sure I left with a copy of ¡Let Freedom Ring! If not, I bought it not long after, and have been sure to buy all of his subsequent and previous albums in the years since.

Chuck Prophet, you see, turned out to be a practically perfect cult artist, in the best sense of someone who has at best a moderate fan base, but one that is willing to lay down and die for him. At some point I spotted a review that called him “the indie-rock Tom Petty,” and that was sort of right in terms of his musical tastes and vocal style and attraction to songs about noble losers, but it also gives him short shrift: Petty, for all his undeniable greatness, never wrote a song cycle about San Francisco that includes shoutouts to hometown heroes as diverse as Harvey Milk, Willie Mays, and the strip-club-baron Mitchell brothers, whose partnership only dissolved when one shot the other to death. One of Chuck’s signature moves is to build a spiderweb of imagery to wrap his stories in, then undercut them with a punchline, as in “Hot Talk” off ¡Let Freedom Ring!:

I said, “Your laughter’s like a drug to me,

I only wish it weren’t at my expense.”

She said, “It ain’t costing you a dime.”

I said, “I know it’s not, that’s not what I meant.”

Or, even more directly-indirectly, in “Coming Out in Code,” off the tremendous Bobby Fuller Died For Your Sins:

You can say that I’m well-traveled

I’m a pauper, I’m a king

They call me Willie Wonka boys

You tell me what it means

Have you seen my candy man

Does anybody know?

I’m speaking to you from the heart

But it’s coming out in code

While waiting out the pandemic and the return of live music, I’ve been eagerly gobbling up Chuck’s email newsletters (no one, except perhaps the sainted Rennie Sparks, has better mastered the form) and listening to him spin records for Gimme Country radio on Friday afternoons. (His show is not mostly country music, or at least not what one would narrowly consider country, unless you have enough room in your big tent for Waylon Jennings and the Rubinoos, both constellations in his personal pantheon.) He was the host of the video anthology that Hardly Strictly Bluegrass put out in 2020 in place of an actual festival in Golden Gate Park, and he’s done occasional exquisite video streams from his and Stephanie’s kitchen, but nothing can take the place of hearing him where I first did: on a stage, with his band, convening the power of a G chord.

I’ve been witness to a lot of bad live music over the years, and even a fair bit of good music where I went home at the end of the night thinking: That was okay, but it wasn’t necessarily worth standing through two opening bands and then dragging myself home on the subway at 1 am for. Every time I’m tempted to skip a show and just stay home instead, I remind myself of that first Chuck Prophet experience, and where I would be today if Josh and Lisa and Mindy and I had gone out to dinner or something instead. There are some wonderful corners of the world just out of sight, and you can never find them if you don’t duck your head in to check them out — which, come to think of it, is one of the things Chuck has been trying to tell us all along.